Malware development: Building malware with 0 imports

Table of Contents

Introduction #

- Modern AV solutions primarily work in 2 ways:

static and dynamic analysis. Static analysis involves detecting known malicious signatures by comparing them with a database of known malicious signatures. It also involves identifyingsuspicious characteristicsand patterns with how the malware behaves by analysingbehavioural signatures. Dynamic analysisinvolves monitoring the program’s behaviour in real-time to determine whether it is malicious.- This article primarily focuses on the first method, looking at techniques that would help us break

common signaturessuch assuspicious strings and importsthat a malware has. We begin by understanding how exactly PE files resolve imports, how various PE data structures such as the IAT work, and how we can build malware that has 0 imports by dynamically resolving all windows APIs.

Static Linking #

- When creating a program using Windows APIs, the functions in your program are linked against the respective import libraries.

- The operating system’s loader will resolve the functions’ addresses at the time the application starts (compile time) and will not run if there are missing functions.

Dynamic Linking #

- Using

GetModuleHandleandGetProcAddressallows you to resolve function addresses during the execution of your program, i.e., atruntime. - This does not create a hard dependency on a DLL and when the DLL or the function is missing, your application can

handle the error gracefully, perhaps bynotifyingthe user orfalling back to alternative functionality. - When using dynamic linking in developing malware, the malware will not directly reference any suspicious imports in a recognizable way until it is actually running.

- We will use this technique to build malware with virtually 0 imports!

How does dynamic linking work? #

- When a program starts, PE loader (responsible for loading PE files from disk) inspects the binary file, identifying external libraries that it depends on

- The external libraries are located and loaded into memory

- The program contains symbols or references that point to the functions and data contained in the external libraries

- The PE loader resolves these references by updating the program’s memory addresses to point to the corresponding locations in the loaded libraries (symbol resolution)

- The program can now call functions and access data from external libraries as if it were part of the program

- To accomplish this, various

Windows data structuresare involved:

Import Directory Table #

The import information of a PE begins with the

import directory table. This generally entails various Windows structures such as pointers to the Import Lookup Table and the Import Address Table, which resolve addresses within imported DLLs.Some of its key components are described below:

Image Import Directory #

- This is a data structure that is located within a PE file. It plays a crucial role in dynamic resolving of functions and APIs, by allowing programs to import and utilize external libraries during runtime.

Structure of the Image Import Descriptor #

- The structure of the IID in a PE is defined as follows:

typedef struct _IMAGE_IMPORT_DESCRIPTOR {

union {

DWORD Characteristics;

DWORD OriginalFirstThunk;

} DUMMYUNIONNAME;

DWORD TimeDateStamp;

DWORD ForwarderChain;

DWORD Name;

DWORD FirstThunk;

} IMAGE_IMPORT_DESCRIPTOR;

typedef IMAGE_IMPORT_DESCRIPTOR UNALIGNED *PIMAGE_IMPORT_DESCRIPTOR;

- The main elements we are concerned in are:

OriginalFirstThunk- stores a pointer to an array of function names or ordinals (numeric values that are associated with functions) which are located in theimport lookup table.Name- holds a pointer to the name of the imported DLL.FirstThunk- points to an array of function pointers, stored in theimported address table. These function pointers will be updated with the actual memory addresses of the functions in the imported DLL.

Import Lookup Table (ILT) #

- Also referred to as the Import Name Table (INT). It is a table of function names/references that tell the loader which functions are needed from the DLL being imported.

- It is especially useful in function forwarding, where function calls are redirected from one DLL to another for the purpose of delegating other functions to other DLLs

Hint/Name Table #

- This structure is defined in the Windows Internals header file

winnt.has shown below:

typedef struct _IMAGE_IMPORT_BY_NAME {

WORD Hint;

CHAR Name[1];

} IMAGE_IMPORT_BY_NAME, *PIMAGE_IMPORT_BY_NAME;

- Hint is a number that is used to look up a function. It is an index to the export name pointer table (contains pointers to functions exported from a DLL)

- If the index lookup fails, a binary search on the name is performed on the export name pointer table to find the function.

Import Address Table (IAT) #

Similar to the ILT in that it contains addresses of functions and data items that are imported from external dynamic-link libraries. It differs because the IAT is overwritten with the actual addresses of imports during the program runtime.

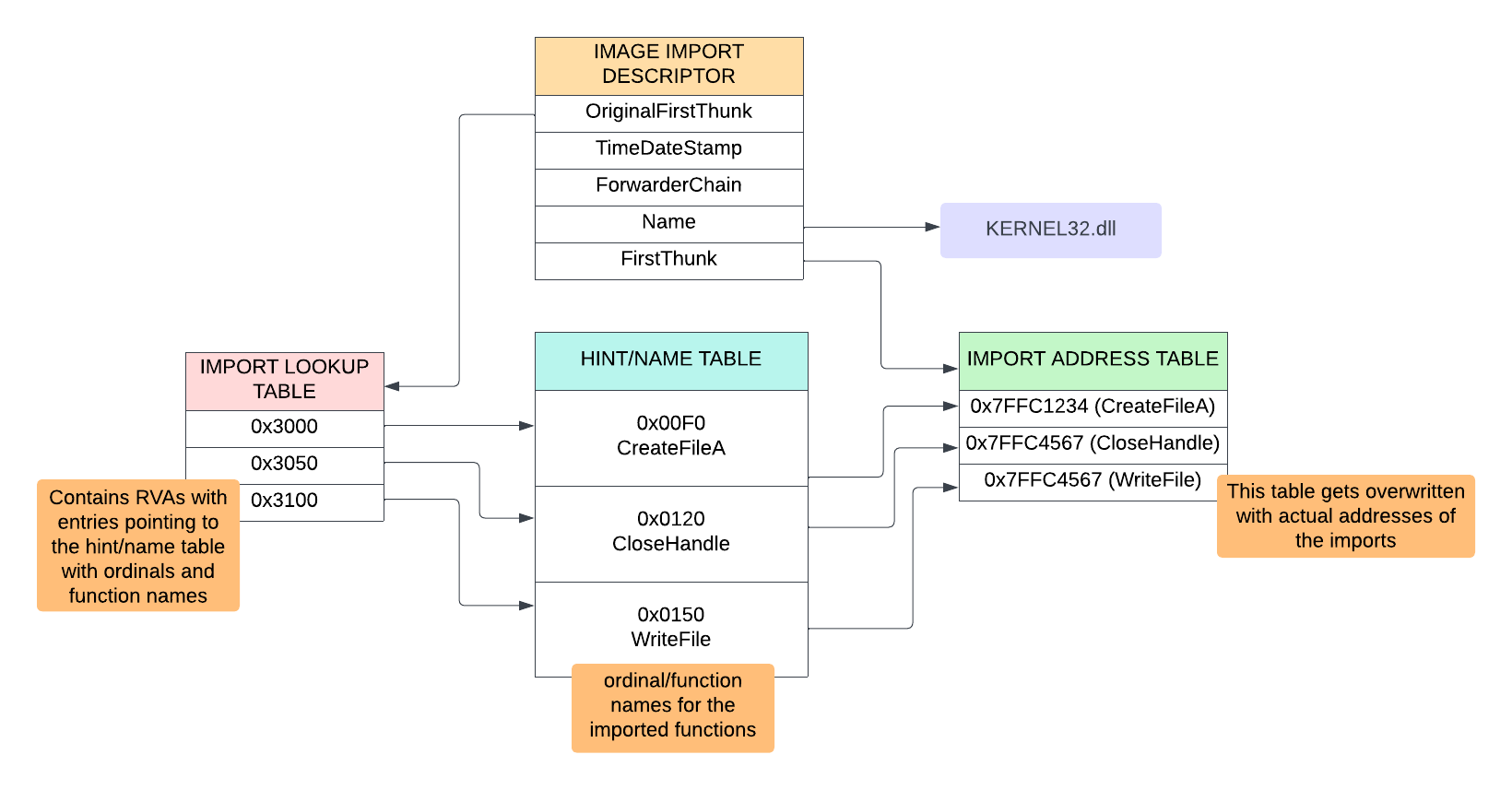

The functioning of the Import Directory Table can be summarized as shown in the diagram below:

GetModuleHandle & GetProcAddress #

GetModuleHandleis used to retrieve a handle to a given module. The module can be a DLL e.gkernel2.dll. The handle can be passed to GetProcAddress to retrieve the address of an exported function from the DLL.In summary, the two are used to

locate function addresses. Instead of statically linking to functions, which can be easily detected during static analysis, we can use these 2 functions to dynamically resolve function addresses at runtime.This means that malware does not have to reveal which functions it intends to call.

Their implementations are as follows:

Implementation #

- We are going to integrate

GetModuleHandleandGetProcAddressinto an example from our previous blogs. - Before we proceed, let us see a simple example using MessageBoxW API and how we can dynamically resolve that API at runtime.

- Let us break it down further to understand what is happening:

Line 6

- We begin by obtaining a handle to the DLL that contains the functions we will utilize

HMODULE user32Dll = GetModuleHandle(L"user32.dll");

Line 9-15

- We proceed to define a new data type using

typedef. The data type being defined is a function pointer that has a signature exactly like theMessageBoxWAPI. The function pointer is of typeWINAPI - GetProcAddress is used to locate the

MessageBoxWfunction address from the DLL. It returns a pointer of typeFARPROC, a generic pointer to a function in a DLL. - Since we now have a function pointer called

pMessageBoxW, we need to typecast it so that the compiler knows how to handle the pointer i.ecalling convention, paramters, return valuethat the MessageBoxWFunc function expects.

typedef int (WINAPI* MessageBoxWFunc)(

HWND hwnd,

LPCWSTR lpText,

LPCWSTR lpCaption,

UINT uType

);

MessageBoxWFunc pMessageBoxW = (MessageBoxWFunc)GetProcAddress(user32Dll, "MessageBoxW");

Line 22

We finally invoke the

pMessageBoxWfunction.If we apply the same logic to our shellcode execution implant, we end up with the following:

- There are 2 issues to address with this kind of implementation.

1. Strings Obfuscation #

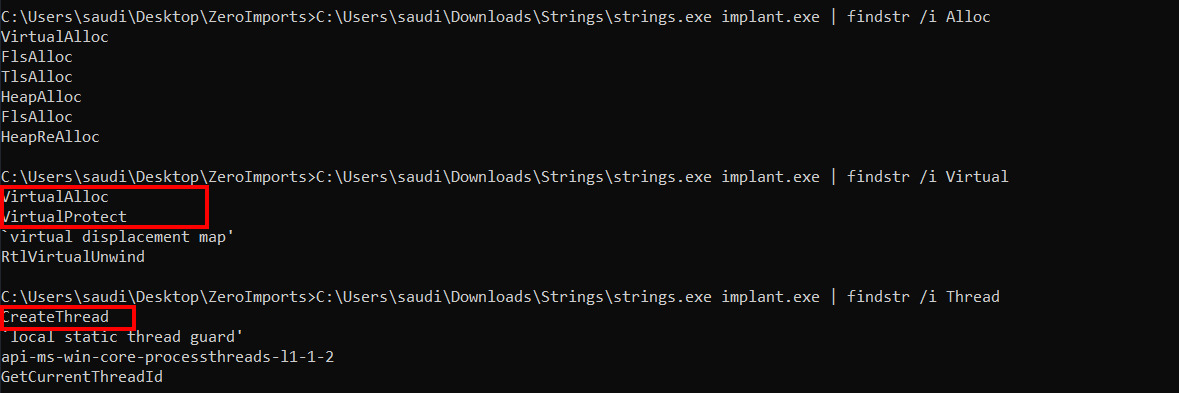

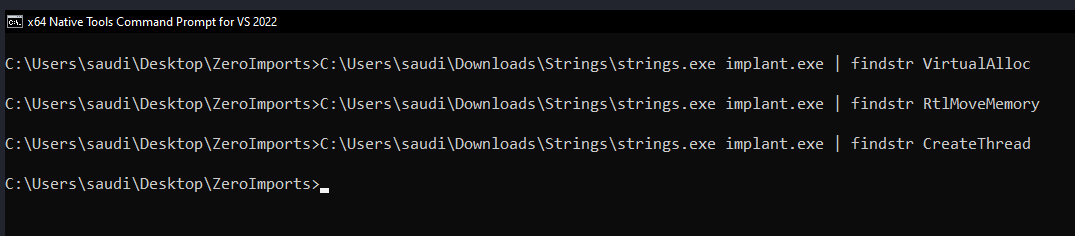

- If we check the strings on the compiled program, it reveals API strings that were used in the program (line 41 - 44). When an antivirus is performing static detection, the suspicious strings will get picked up.

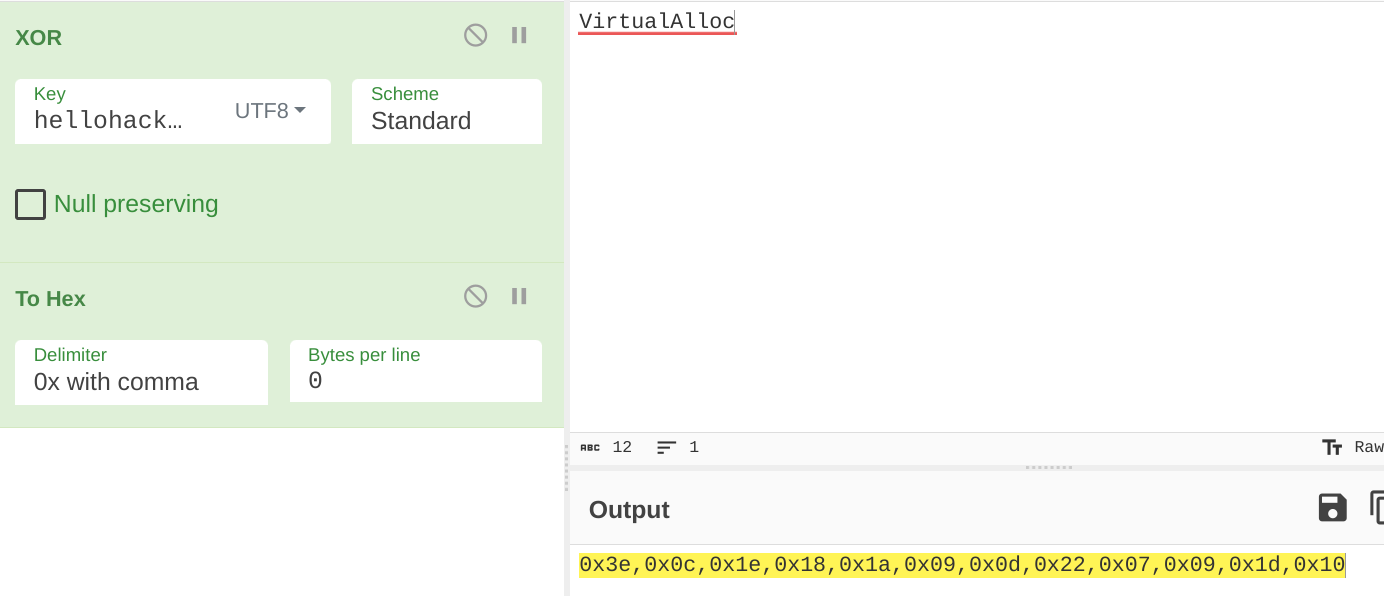

- We can get around this by encrypting the suspicious strings using XOR, and decrypting them before using them.

- You can use Cyberchef to perform the strings encryption.

- The final XOR implementation is as shown. Note that I added null-terminating characters

0x00for our strings:

- We successfully get rid of all suspicious strings.

2. Reducing all our imports to 0 #

- Our code statically links to GetModuleHandle and GetProcAddress Windows APIs. When viewed in the Import Address Table, we see these 2 which may raise suspicion with some antiviruses.

- The workaround we cover in this blog is to link a manual implementation of the 2 APIs to our program so that instead of relying on the Windows APIs, we use our implementations that parse the various DLLs and locate our needed functions.

- The main chunk of the implementation has been provided below. The code might look complex but it’s actually straightforward if you understand the purpose of

GetProcAddressandGetModuleHandle. - The implementations of GetProcAddress and GetModuleHandle work as follows:

hlpGetModuleHandle Function #

- This function retrieves the

Process Environment Block (PEB)for the current process. This structure contains information about the loaded DLLs in a process. - If no module has been provided, it returns the base address of the calling module.

GetModuleHandleAPI works exactly like this, where passingNULLas the module name retrieves the handle to the file used to create the calling process (usually the executable file) - The

PEBcontains a structure called LDR which has information about the loaded DLL within a process. It has a linked-list calledInLoadOrderModuleListcontaining names of our modules, which we iterate through to find our desired module. - We compare the

BaseDllNameof each module entry withsModuleNameand return the base address of the module we find. If no match we return NULL.

hlpGetProcAddress Function #

- This function parses the main headers and structures from the obtained module handle to access information about functions that have been exported by a module.

- If

sProcNamehas been provided as an ordinal, it directly looks up the address in the Export Address Table using the ordinal. - If

sProcNameis a function name, we search the table of function names to find a match. - If we find a match, we retrieve the function’s address and return it, otherwise, we return NULL.

Project Files #

- The complete project files are linked here

- The final implant code fully encrypts all suspicious strings and dynamically resolves all our functions:

Compilation and Running #

- The project includes a compile.bat file to help with the compilation and linking of the implant and helper files. You can do it as shown:

Verifying Zero Imports #

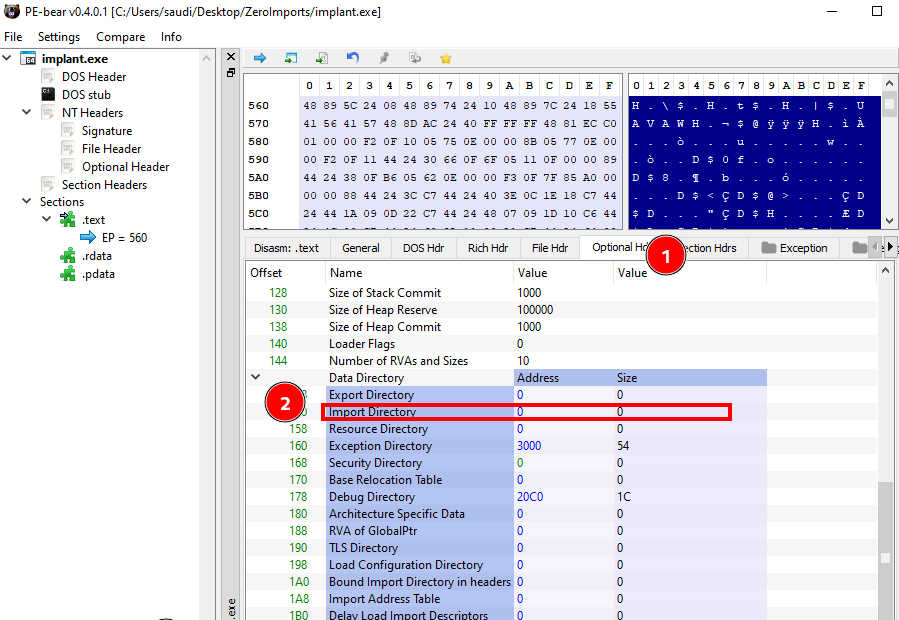

- If you open the compiled implant on PEBear, the imports are zero as shown: